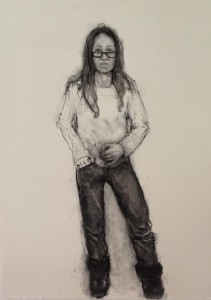

The truth is I was deeply terrified when I finally got back into my studio in 2013; after a month in the hospital and several weeks in a physical rehabilitation center, and a definitive diagnosis of MS, it would be months and months and months of slow recovery before I felt well enough to go back to work. When I finally did, I was terrified that the illness—which I barely understood and, actually, still barely understand because apparently no one really does—would impair my ability to draw and paint and imagine. The first drawing I did when I returned to my studio was Self-portrait (after MS Diagnosis) and it felt like I was doing one those drawings that art schools used to make applicants do (do they still?)—draw the bicycle, or some such thing—just to see what you’re capable of. Could I still draw a hand? Could I draw myself standing on my own two feet? (One of Dr. Boschi’s first remarks when I had told him about my initial symptoms of MS was: “Well, what comes first to my mind is you feel that you can’t stand on your own two feet.”) Could I still imply ineffable feelings—confusion, longing, vague terrors? It helped to do that drawing; it helped me believe that I could go on painting and drawing and writing even if I had MS.

Multiple sclerosis is a very frightening diagnosis to receive—the words themselves are mysterious, meaningless to the lay person, and ugly sounding. The fact that there are those two words together doesn’t help in understanding either of them. Like the words “childhood sexual abuse” and “incest,” these are words that seem to arise out of a vast swamp of human frailty and generations of deep-seated illness. In my case, those latter terms—such as “sexual abuse,” “incest,” “dysfunctional families”—were learned and applied so long after the experiences themselves occurred in my life that it always feels awkward, anachronistic, and almost spurious to use them. Those particular words were certainly not in use when I was growing up, and, more to the point, I was sexually abused by my father long before I had a functional vocabulary let alone one that was so advanced. The fact that this habitual domestic violence began before I had any words for it, any sense of its meaning, its morality or lack of such, made it impossible for me to comprehend it, let alone talk about it. Decades would pass before I could attach words to the experience; and it is only recently—actually only since my most recent MS attack in October 2014—that I felt a compelling need to talk about these experiences explicitly and overtly, rather than in a coded, implicit way in my artwork. My need to do so is, of course, in large part selfishly motivated—I feel that in so doing I take the burden off my internal organs, my autonomic nervous system, my unconscious, my body, my cells—in other words, I hope to increase my chances for getting well. But I also believe that talking about these things in explicit, probing, honest ways is essential to the survival and evolution of the human species. And, I simply find the whole concept of somatization fascinating and brilliant—a kind of quantum mechanics of the psyche.

A. M. HOCH, Three Floating Heads, oil paint and markers on bubble wrap, approximately 38 x 72 inches, 2012

Soon after we began our work together, Dr. Boschi said something that transfixed me; his words, if I remember correctly, were: “The human psyche has the intelligence to target specific parts of the body, particular parts of the cells, with more precision than any smart bomb could ever be designed to do.” I felt there was a profound truth in this remark, revealing an insight that penetrated to the core of my being, but I had never come close to putting into words. For decades, I’ve used cellular imagery as a metaphor in my artwork, in all kinds of mediums, so any mention of cells and our unconscious awareness of what’s going on inside them, incites a kind of riot of thoughts and feelings in me. And Dr. Boschi’s remark had such far-reaching implications—in all kinds of fields, let alone in my own life and work in particular.

A. M. HOCH, Connected Heads in Four Parts, mixed media on paper; 153 x 112 cm (60 x 44 inches), 2010

Prior to my first MS attack I was working on a series of drawings, paintings and installations associated with The Diary of a Young Boat. When I was in the hospital, trying to understand the strange foreshadowing in The Diary of my future MS symptoms, one of my friends commented that he had been struck by how much my drawings of the previous year had reminded him of ganglia; the fact that at the time I made those pieces I was suffering from a hidden neurological disease was a bit uncanny. But that was only the beginning of the uncanny correspondences between my MS onset and references to analogous fictional events in The Diary of a Young Boat. It became like a detective story trying to piece it all together—sometimes it seemed to border on the insane or the inane, like when Beatles fans began playing lyrics backwards and finding all kinds of hidden clues about Paul McCartney’s fictional death. Strange puns and double meanings seemed to suddenly appear everywhere. For instance, the lesion on my spine that was causing those first bizarre symptoms and numbness was located in the D9 vertebrae; “D-nine” sounds a lot like “denial.” And it was in entry # 9 in the Diary that the young girl’s first toe falls off. I could go on and on, but I won’t here, because, like dreams, the details are of most interest and importance to the dreamer. But what I was able to say out loud to Dr. Boschi many months later is perhaps of objective importance: When the cortisone treatment I received in the hospital caused sensation to return to my genitals, undoing the temporary liberation the MS had given me, my unspoken, barely conscious feeling was: They’re messing up my masterpiece! (In reading this, I realize how perverse that sounds, but the feeling of relief and awe I experienced when that part of my body was neurologically severed from the rest of me was remarkable.) Some very hidden part of me felt that my illness came from an unfathomably deep and brilliant part of myself.

Writing the text for the Diary of a Young Boat was a breakthrough for me as an artist and as a person, but it was in code. It was a piece of surreal fiction that allowed me a kind of artistic quantum leap and personal exorcism, but its relation to my onset of MS also demonstrates a remarkable truth: that both art and illness are crucial ways for our unconscious to communicate with our conscious minds and with other human beings. But explicit communication—in a shared verbal language—of the truth of our human experiences may provide a clearer way out of our own unique hells, a further transcendence of whatever personal traumas and prisons we are shackled to. Some part of me knows that illness CAN be a transformative experience, not a punishment or a curse, and it’s in this spirit of curiosity and expansiveness that Sarah Kornfeld and I will begin our online conversation, to be shared with you on this website (eventually, as health allows) in Theater in the Cloud, and on Ms. Kornfeld’s website cultureWAVES, and in God knows what other forms we can come up with!

Find more like this: Updates