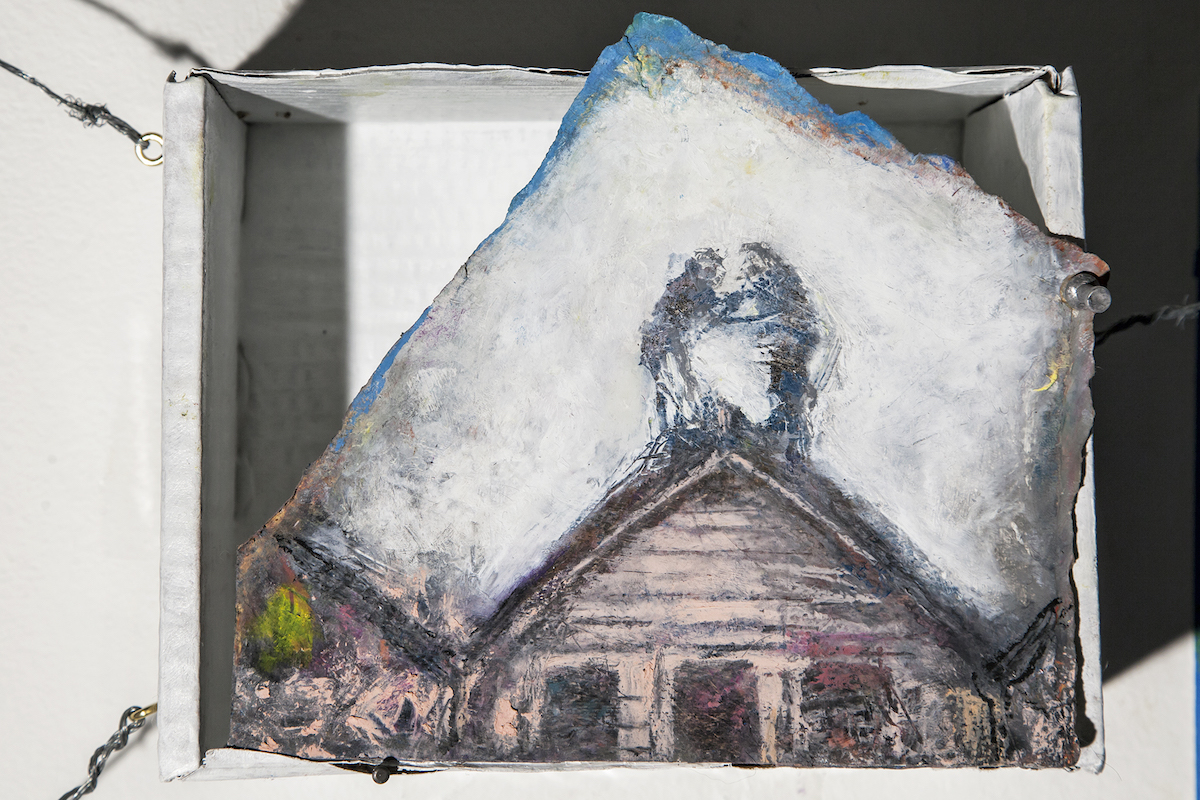

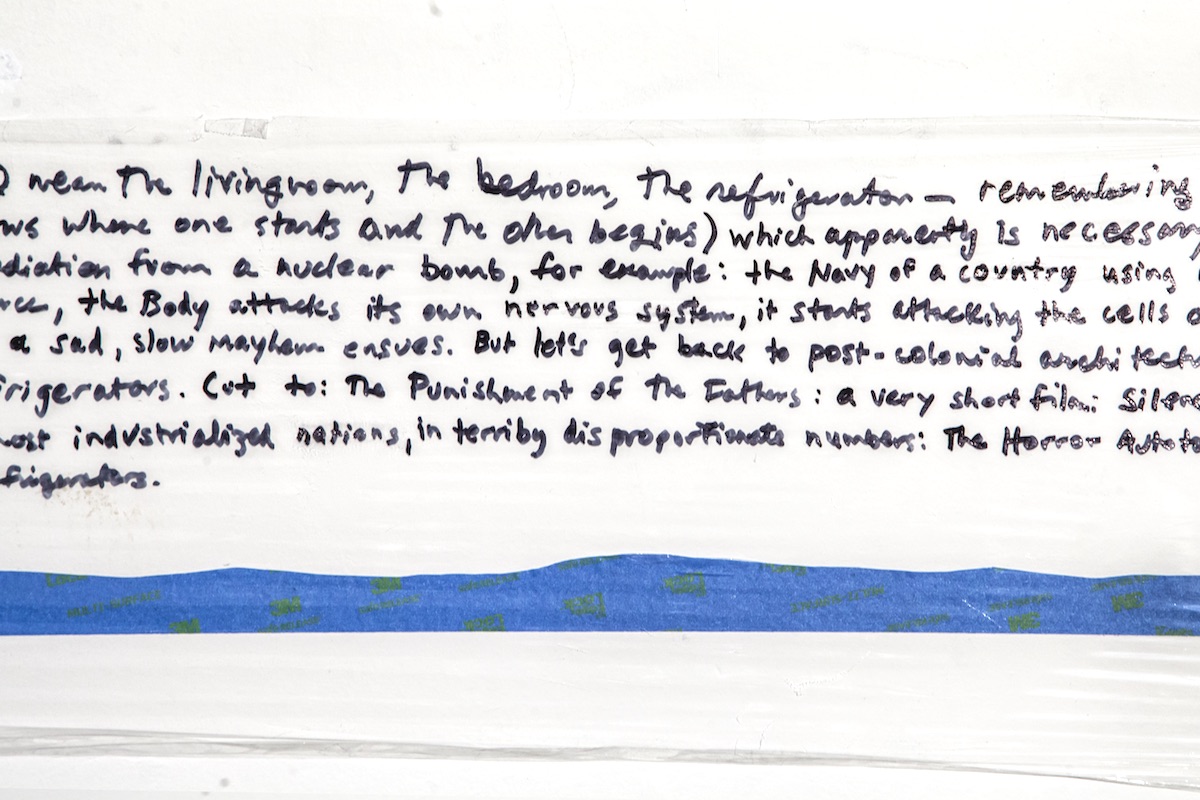

The Horror Autotoxicus was the name given to autoimmune disease by the German scientist Paul Ehrlich, who discovered it back in the 19th century. The name conjures up a primordial terror, a monstrous thumping force; it feels apt to me. In diseases like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, the body attacks its own—its own cells, its own tissues—and in the epitome of horror, you discover the enemy is inside your own house: Suddenly the electricity cuts out; you can’t get your legs to work; your mind is ransacked.

In its failure to distinguish between “self” and “nonself,” as Ehrlich described it, the illness wages a self-defeating war against its host that can go on indefinitely. There is no invading army, no marauding microbes: somehow these illnesses invade from within. It is the stuff of science fiction, or the familiar story of how a civilization crumbles; there is an operatic irony at play in The Horror Autotoxicus.

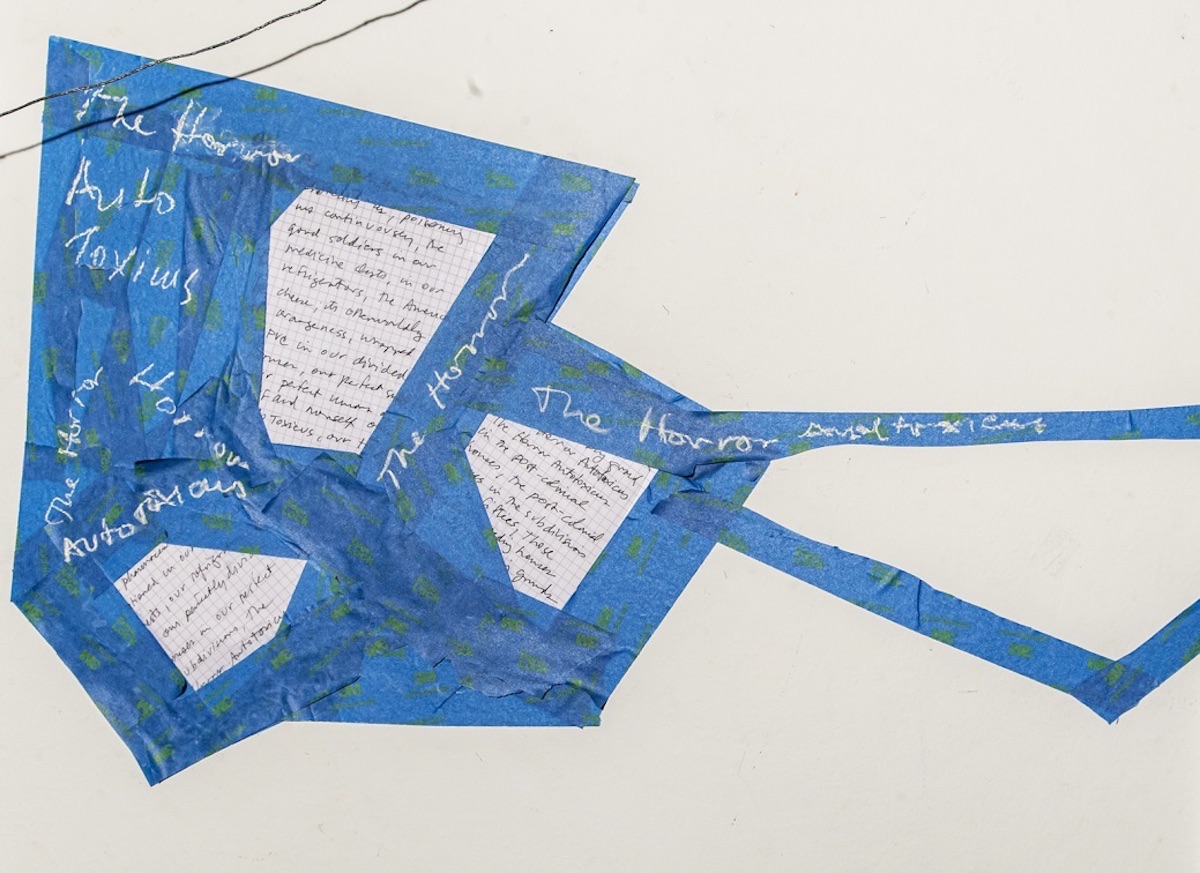

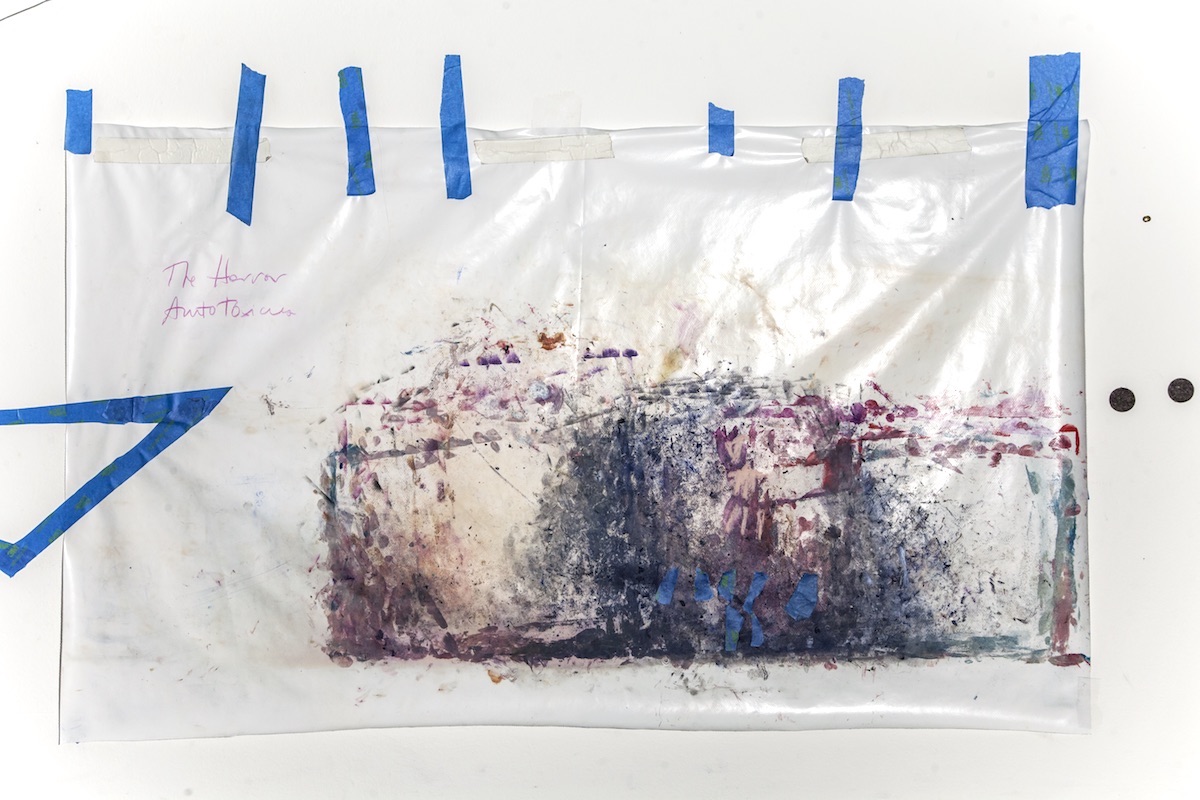

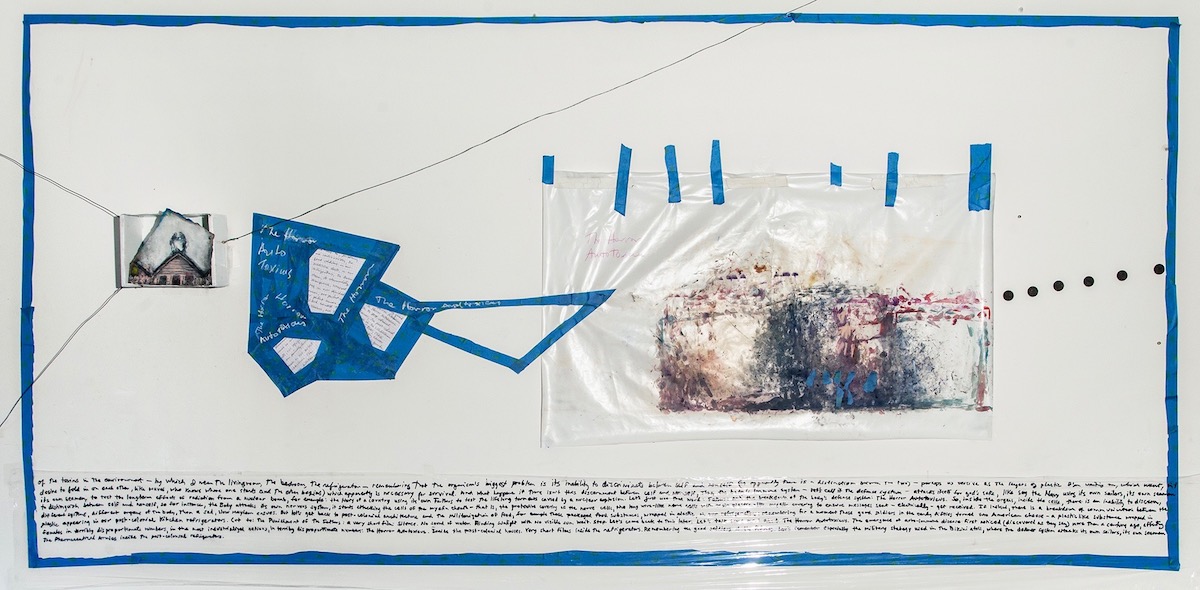

Autoimmune disease is the perfect flower of our post-colonial, post-industrial society—the most apt embodiment of our culture’s pathologies, as hysteria was for Victorian culture. Disease, like poetry, operates on many levels at once, working on the miniscule and the grand, the physical and the emotional all at once. So this series, entitled The Horror Autotoxicus, began as a get-well bouquet to myself when I returned to my studio after years of debilitating relapses and new autoimmune diseases. This was my wobbly first step at “sense-making.”

In her article on the invisible women artists in our midst, Lynn Steger Strong writes:

“It is a sort of madness to decide to make things. But it is a fury wholly inside one’s head, contained. Most people who make things, I would argue, are compulsively trying to control, attracted to edges and the limits of materials—paint, for instance, or words. The things that come as a result of these compulsions are a form of sense-making: a scaffolded, cut-and-pasted, formally restricted offering. And then it is received, by the public, in their own way, if it’s even noticed.” (“She Was Sort of Crazy: On Women Artists,” The Paris Review, January 31, 2019).

Multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and god-knows-what-else, have left me feeling lost, invisible and tongue-tied; The Horror Autotoxicus, like my other series, is a form of sense-making for me; it is my own sort-of-crazy map—scribbled, personal, coded notes for where this series is going. Maybe nonsensical to others, but I’d be lost without it.